Unsettled

by Colin Leonard

It was the flashing lights that brought Mrs. McGarry to the door, not the noise of the ambulance. She was quite deaf without her hearing aids. She stood on her doorstep, hunched against the cold. In her porch, a rusted wind chime swayed gently and whispered, mimicking all the other neighbours outside their homes. The Gardai were going house to house. When the young, uniformed man came to hers with his notebook and his solemn face, she brought him inside so she could stick in her clunky flesh-coloured aids.

“Did you know them?” he asked her as she led him towards the kitchen.

“I knew the O’Sullivan man’s family. Most of them are gone now. He and the wife moved back here before the children were old enough to go to school.”

She waved the kettle at him but he shook his head.

“No thanks,” he said. “I have a lot to get through tonight. Have you always lived here then?”

She filled the kettle anyway and went rooting in the press for the good cups.

“No, I was born in County Mayo but I’ve lived here for as long as this town has existed.”

“Oh?” He resisted the dubious comfort of a scuffed wooden chair. “How do you mean?”

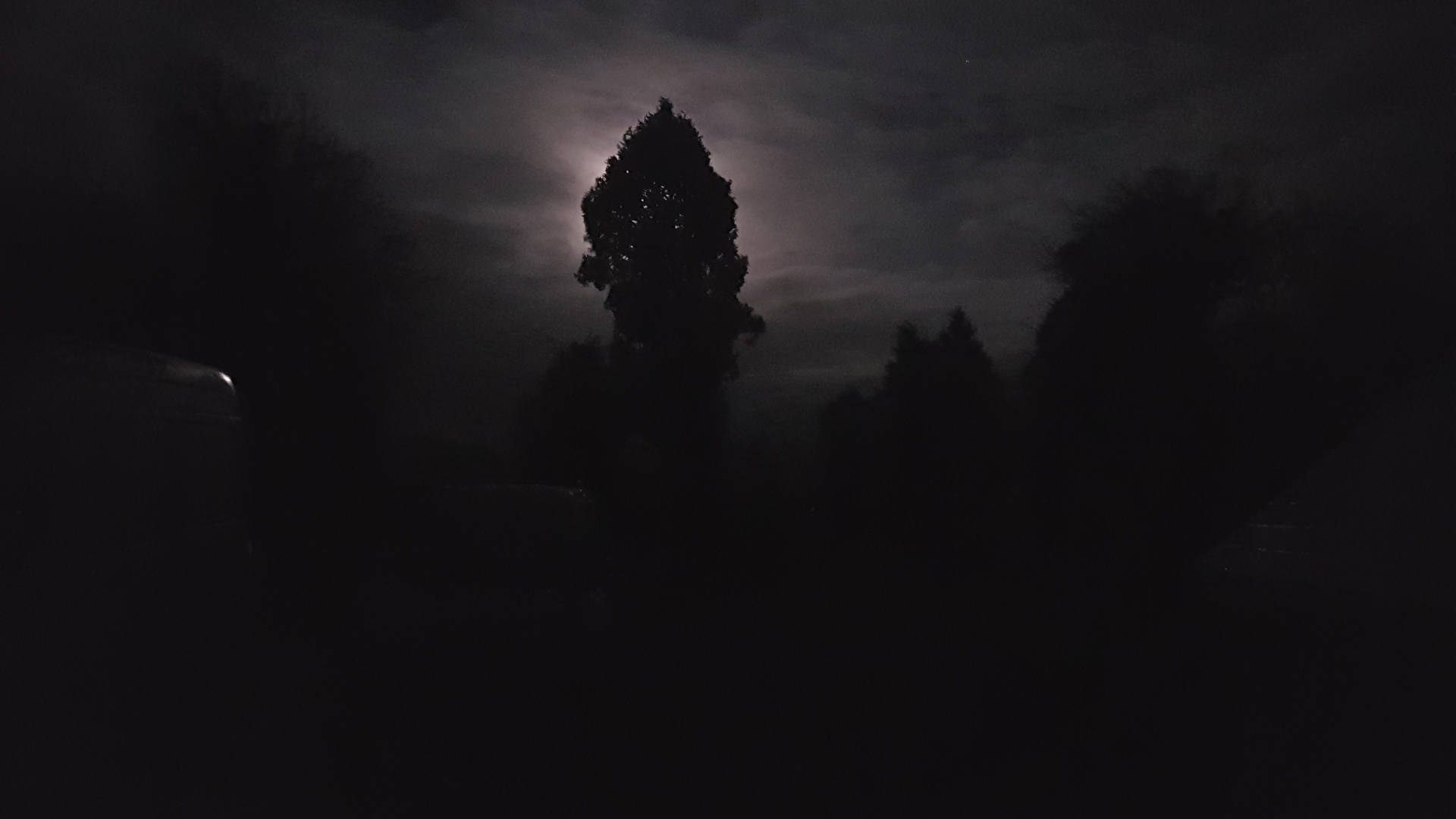

Outside the kitchen window, a figure moved through the shadows and the old woman made the sign of the cross.

“Reporters,” said the Garda. “How do they find out so quickly when a tragedy happens. He’ll be knocking on your door after I leave. Don’t let him in.”

Mrs. McGarry spooned tea leaves into a stainless steel pot.

“I’m used to a different kind of ghoul hanging around here. I see them outside, prowling around the edges of the houses. Even if the others can’t see them, I know what they are.”

“I’m sorry, I’m not following you.”

“You know how this town came about, don’t you?” she said. “It wasn’t always here. There were just a few scattered houses before we all arrived back in the thirties. They moved us from the Irish speaking parts of Kerry and Mayo and Donegal. Poor places, starving places, even then. I was just a wee child when my parents were given this house. I’m eighty-three now. They gave each family a bit of land to work. It wasn’t great land but it was better than what we came from. There was no future for us back there. But if you ask me they shouldn’t have gathered so much misery together in the one place. More houses got crammed onto the bits of land we were given. More houses were added on every year, more bad memories all collected together.”

The Garda flipped a page of his notepad even though he hadn’t written anything down.

“The O’Sullivans, though,” he said. “Was there anything strange about them? Did you ever see them, eh…was there any violence that you noticed?”

“You shouldn’t just build a town like that, like you just decide it goes here and then you fill it with people, it’s not natural. Bad things have always happened here. The people they stuck here were haunted, they brought ghosts with them. Poverty, starvation, even the language we brought with us is a ghost.”

“Did you ever see them act violently with the children?”

Outside the window, the Garda could see rubbish bags lying against the walls of the houses and the fences, soft shapes whose edges moved hazily in the poor light from the neighbours’ windows. The doorbell rang. He looked at his watch.

“I don’t like it here,” said Mrs. McGarry. “I never have. A badness makes its nest here, gets into the people, even the new families.”

The cups were encircled with blue Chinese landscapes. Her withered hands shook as she brought them to the table.

“But sure where else could I go? The place I was born isn’t there anymore, it’s just rocks on a hill now.”

The Garda closed his notebook resignedly and stepped back out into the tiny hallway. The meter box on the wall looked very old, he could remember ones like that from his childhood.

“Will you not have your tea?” she said.

The letterbox flipped open and a weedy voice called in through it.

“Hello, Mrs. McGarry? I’m with the Herald. Do you mind if I have a little chat? Just about the couple who killed themselves tonight.”

“I’ll get rid of him,” said the Garda.

“There were awful things deep in the people who came here first; the likes of my parents, passed onto them from their parents. Things like that don’t just disappear you know. They blow in the breeze until they settle and grow in the soils of sorrow.”

The Garda opened the door and saw a saggy-clothed man pressed against it with a pen in his butty fingers and his own notebook poised.

“Leave her alone,” he said. “She’s just an old woman. She didn’t know them.”

The journalist looked up at him, his face bubbling with animation despite the large official hand that steered him away.

“Is it true what they did to their children, Garda? Is it true what they did?”

Mrs. McGarry was at the doorstep now too. Her eyes squinted at the residue of commotion that had filled the neighborhood but they didn’t linger on any of the people who were still standing around in the wake of the departing ambulance. She watched instead the spaces between them.

“Awful things happen here. It began in the Famine, you see. When you’re starving, you’ll eat anything. We brought Famine ghosts here with us all those years ago. They gnaw away inside our bellies.”

The End